2022 reflection as a product manager

Hi there, thank you for being here, at this point in time and space.

I spent the past few days thinking about what I’ve learned over the past year. In 2021, I stretched my thinking on thorny topics such as product strategy, enabling context and synthesizing how frameworks may be combined.

But I didn’t write a single blog post in 2022, because I wanted to move away from abstraction and synthesis and get closer to more simple ideas. Specifically, I want to put simple things into practice, extensively. So far, I’ve been able to take some simple ideas very seriously. And I think of that as a great success.

I won’t go into too much details or nuances, I just want to circle around and re-iterate the central theme of this blog post. That it isn’t easy to do simple things, but you should try to make it easy. Even when it’s difficult, re-organize yourself and the team in whatever ways necessary so that you can still focus on doing simple things.

Make it easy to do simple things

When you’re working within a platform, the most impactful thing may lie outside your direct area of authority, especially when the product is technical and without a user interface (e.g a cloud infrastructure system). You may have to touch on user journeys that span across different modules in the platform to make people even aware that your product exists.

Earlier this year, I was concerned with launching a new product within our platform and facilitating its GTM movement. Several months later, we sat down to review what were the leverage points that could unblock growth. The product’s presence within the platform was weak, and its activation rate wasn’t satisfying. Admittedly, these two things could have been unrelated, but I made a hypothesis that they were related: If people don’t know about a product, naturally they wouldn’t start using it.

I shared the hypothesis with the team and got buy-ins from other PMs to change the platform’s onboarding flow to one that guides users to perform a core action in my product. The monthly usage increased almost four times. And ARR showed a significant increase. Some might even say that it was obviously going to work. But to me, it definitely wasn’t obvious until we observed the result.

Why didn’t I do that sooner? Prior to that point, we had to focus on delivering some features that enabled completely new capabilities which were requested by many prospects. I think the positive result of the experiment were not merely due to improving the onboarding flow. Had we not delivered the features first, the impact of improving the onboarding flow would probably have been much less immediate. Reality is often messy like that. So while I’ll keep talking about simple ideas in this blog post, I’m well aware that they manifest in very complex and confounding ways.

But nevertheless, it was executing a simple idea amidst of complexity that ultimately worked out well. Doing simple things does not guarantee success, but doing enough simple things would compound and increase your likelihood of success.

What made me more willing to act on the bet was that the ability to dynamically adjust the onboarding flow on the fly (using a tool). It made experimenting much cheaper. I was initially worried that the use of such tool would steer us away from optimizing the UI/UX itself. But it helped demonstrate quickly that solving the problem we identified created impact.

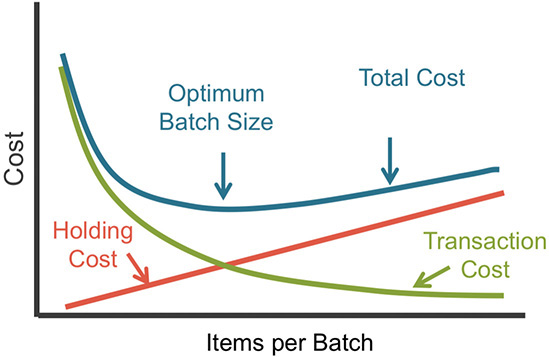

To summarize, I’d like to borrow a principle from the manufacturing world:

Or in a more PM-friendly language, lower the cost of doing experiments by using tools that let you modify parts of the products easily, and you would be more naturally inclined to do more experiments. Sometimes, a quick experiment can produce a quick win that justifies more costly experiments, especially if you’re in a more conservative environment. And experiments may sound heavy. They’re really not. They’re often very simple things that we think can work.

Make it easy to do simple things.

But even when it’s difficult, focus on doing simple things anyway

Taking simple ideas seriously can be the path to impacts. But the difficulty comes from the fact that everything in a company is situated within organizational, interpersonal and personal constrains that are reflective of the reality in which it manifests.

Perhaps your company isn’t one with a culture of trial-and-error. Perhaps your product and engineering departments don’t get along with one another, which makes shipping minimum viable changes difficult. Perhaps you don’t feel like you want to learn to navigate organizational complexity and politics at this point in your career. Or all of these things may happen at the same time.

But you need to do simple things anyway. In fact, I’d argue that in an organization with more constraints, doing simple things would create more impact because the collective would likely be too concerned with organizational complexity and lose focus on simple ideas.

Take the above example: improve the onboarding flow and activation increases. As an avid reader and a product manager, I am aware of how obvious that sounds. There are a lot of practical questions you have to answer. Some are essential questions, like “what is the definition of your Aha moment?”. But in all honesty, just pick your best guess and go with it. Then learn from data and iterate again. My initial definition of Aha moment was ridiculously simple. But after just a handful of iterations, we got great results.

Let me share another story about simple ideas.

A few months ago, we decided to improve a particular dialog within the platform that people use to schedule their tests (our product is a software quality platform). After examining historical data and the user journey when they first come to the platform, we determined that a huge friction point would be when users schedule their first tests. The old dialog induced small but numerous cognitive loads on the users to complete the task. Our bet was that reducing these cognitive loads would mean a higher task completion rate and thus a higher activation rate.

But the act of scheduling is something people would engage in repeatedly even after their first tests. Many functionalities on that interface belong to other modules owned by other product managers. And my team isn’t the original owner of the dialog. These factors amount to a certain degree of reluctance, both from our side and from others. But we pulled through and pitch our hypothesis to other teams to convince them that the problem was worth solving.

We were able to get buy-in from other product managers to proceed. The product designer was given the problem statement, business constraints (time, what problem we will not solve, etc.) and, most importantly, the freedom to exercise their craft in the solution space. A handful of prototypes were created and reviewed together. Ultimately, we settled on a version that addresses the most important problems in the original design.

In order to de-risk the experiment, the dialog was rolled out to just 20% of our new users. It helped us detect issues in a controlled manner. Early signals showed that both completion rate and time on task were improved. We rolled it out to 50% of new users. The task completion rate almost doubled, and users on average complete the task 10 seconds faster using the new dialog.

It was a simple set of ideas (analyzing the user journey, guess which point creates frictions and derive a solution), but it brought great results. There are of course always nuances when you put them into practice. It’s not easy. But it is simple.

Even when it’s difficult, focus on doing simple things anyway.

Conclusion

2022 was a great year for me, both professionally and personally. I think embracing simple ideas seriously helped accelerate my career and impact a lot. I’ve come to embrace more the complexity and uncertainty of product management, while developing and enriching mental models based on both experiences and absorbing other people’s works.

Finally, I’ve grown a lot in a short period of time by taking on a lot of responsibilities, but I also experienced a lot of stress. While it’s still manageable, I think in the long run it wouldn’t be appropriate. That’s why starting next year, I want to aim at creating sustainable infrastructures around my work so that I can support myself and other people better as a product manager.

It’s been a great year, folks. Until we meet again!